The research landscape has changed dramatically in New Zealand and globally, making partnerships, particularly with industry, critical to delivering community good.

That’s the view of Scott Crawford, Research Operations Senior Manager for Auckland University of Technology’s (AUT’s) Women's Health and Neuroscience Research Programme. AUT has recently begun a multi-year research collaboration with global healthcare technology company Abbott with the goal of transforming how sports injuries involving the brain are treated, especially for female athletes.

“Abbott has pioneered the analysis of blood biomarkers, and we can now take advantage of that expertise with the installation of their ARCHITECT® ci4100 analyser in AUT’s SPRINZ biochemistry lab at AUT Millennium, a hub for many of New Zealand’s high-performance sports organisations and Olympic athletes,” says Crawford.

Alongside Abbott, the research team is also working with health boards, emergency departments at Hutt Valley and Christchurch Hospitals,the University of Canterbury, AUT Millennium, national sports organization, and three other universities here and in Australia.

Crawford says this broad range of collaborative partners is critical to learning more about mTBI in female athletes, treatment options, and returning them to sport.

Why focus on female athletes? ”We know very little about the effects of mTBI on women other than the symptoms can be more severe and recovery takes longer than for males. We know there’s a connection with hormonal differences across the course of a month pre- and post-menstrual cycle. We know even less about the effect on Māori and Pasifika women,” says Crawford.

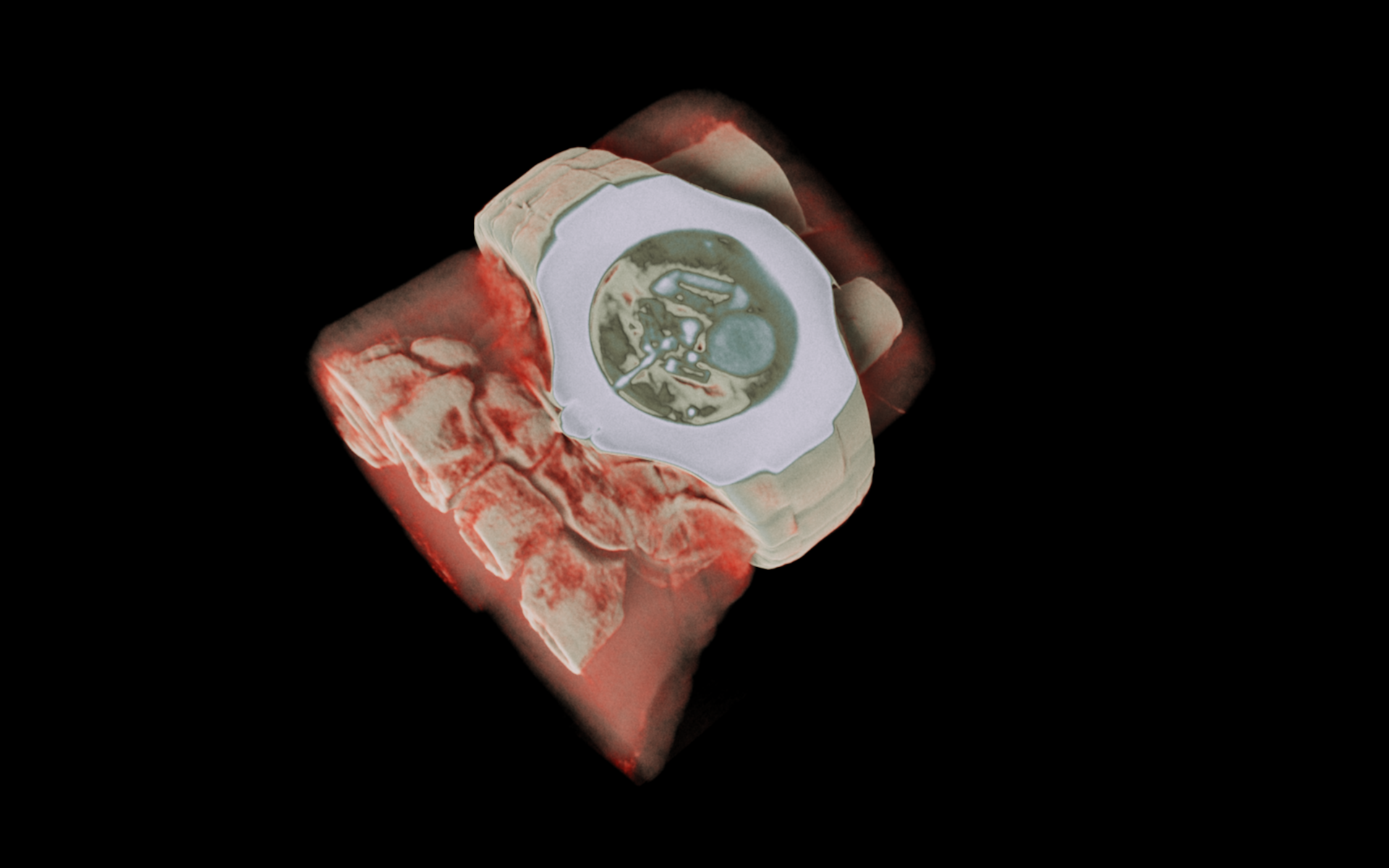

“Injuries from contact sport, which is very topical at the moment, account for about 23 per cent of concussions in New Zealand. In an ideal world, we would identify mTBI within 24 hours of the injury, otherwise recovery can be longer. However, our emergency departments don’t have an effective way of diagnosing those injuries without using radiation-based CT scans,” says Crawford.

A blood sample, on the other hand, offers a way forward. “There is exciting emerging evidence on th euse of blood and hormone levels to detect physiological changes caused by brain injury,” says Professor Alice Theadom, AUT Professor of Psychology and Brain Health, who also directs the AUT Brain Health Research Institute.

Beth McQuiston, M.D., Medical Director in Abbott’s diagnostics business says, “it’s time we adopt approaches that address the unique challenges concussions pose to women. Screening for blood biomarkers released after a brain injury means we can quickly and accurately determine if a CT scan is needed. This improves patient triage and reduces unnecessary radiation exposure.”

Mild TBI can also exacerbate pre-existing mental illnesses because symptoms such as tiredness, fatigue, and confusion are similar. Crawford says if they can show what’s happening by looking at protein markers, then it could indicate the need for further investigation and treatment, something ACC is interested in.

The WHN project team are now looking for two cohorts of women athletes – healthy participants and those with recent concussions who are now recovering. They’ve identified biomarkers for assessing the acute and chronic stages and have developed a programme that will track participants seven times post-injury along with other screening tools.

If the project delivers the results the team are seeking, Crawford says biomarker testing could be used in other situations, such as overcoming the limitations with putting small children through scans. It could also be used with the nearly 80 percent of mild TBI that comes from falls,violence and old age.

.jpg)